Photo by Stringer/AFP/Getty Images

Lou Reed probably would be pissed off to see John Cale mentioned in the first sentence of his own appreciation. But the first thing I recalled when I heard the hard-to-process news of the Velvet Underground singer’s death of liver disease this weekend was an interview with his old V.U. bandmate this summer on WTF With Marc Maron.

In an expansive mood, Cale was describing their early days, after they were introduced at a Pickwick Records session for a rote rip-off pop single Reed had ginned up for the company on contract, a gig he’d snagged not long out of high school, after his head had been scrambled by parentally ordered anti-gay electroshock and then was rotated on its axis by Delmore Schwartz’s poetry lessons at Syracuse University.

Cale and Reed had gotten to talking about literature, and Reed to grousing about the label’s indifference to the real songs he was writing (unbelievably, he’s said “Heroin” was the first), so the two of them took to busking outside jazz clubs in Harlem with Cale on viola and Reed with an acoustic guitar, playing “Waiting for My Man” for the first time on Earth to passersby. Sometimes guys from the block would come up to hassle them, and Reed would shut them down, drawing up his track-star body even as his voice dropped to a threateningly sardonic, “Are we bothering you?”

But what blew my mind most was Cale saying that, a lot of the time, Reed was improvising the lyrics, on and on for hours, describing what he’d done that morning or what was happening right there on the street. “He had the gift,” Cale said. And I thought of the “Waiting for My Man” verse: “Hey white boy, what you doing uptown?/ Hey white boy, you chasing our women around?” Here, it seems, was Reed folding the confronting interruption directly into the song itself, making the street his art and his art the street.

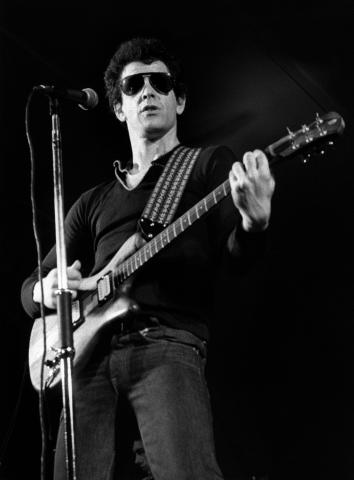

Somebody on Twitter said on Sunday morning, “The world became a bit less cool today,” and, yes, you can’t deny Reed’s influence as a black-and-white photograph, as a shades-and-black-leather motorcycle angel of numbered-street attitude, as a junkie voice too cocksure even to bother half the time to sing, as an acolyte of alleyways and garbage. But it was that extemporizing, in situ mind of his that was revolutionary. Patti Smith and punk and every later branch of conceptual art rock were his direct godchildren, and it’s hard not to hear a pre-intimation of rap, too, in the way his jive patter roved the grid selecting neighborhood characters to transform into icons before moving on, in his instinct for documentary and for matter-of-fact aggrandizement.

Not to say that anybody like the Sugarhill Gang or Run-D.M.C. were among the fistful of people who heard The Velvet Underground and Nico and, as Brian Eno famously said, went on to form a band. The two had nothing directly to do with each other. But Reed was coming up in a similar milieu and put it to use with corresponding savvy. No wonder that even this year, as a 71-year-old geezer, he had no trouble grokking what Kanye West was doing on Yeezus.

But on the flip side Reed also had that education and a missionary intention to bring what Schwartz showed him about what was happening—and not happening—in literature to bear in rock ’n’ roll. For a 1966 issue of the art magazine Aspen, he wrote a sort-of manifesto as a “View from the Bandstand” column, in which he mocked the “college” poetry world for giving awards to Robert Lowell when they should have been giving them to Bo Diddley.

He laid it down straight in a typically bitchy interview with Spin in 2010:

Hubert Selby. William Burroughs. Allen Ginsberg. Delmore Schwartz. To be able to achieve what they did, in such little space, using such simple words. I thought if you could do what those writers did and put it to drums and guitar, you'd have the greatest thing on earth.

He wouldn’t have been able to do it without Dylan of course, but Robert Zimmerman was at heart a capital-R Romantic from the sticks of Minnesota, thinking about Woody Guthrie and Rimbaud, and it took about 10 minutes for the kid actually from New York City to suck up his example and calculate how to make Dylan’s moves look practically old-fashioned. It just took another decade for everyone else to realize it.

Source: http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/music_box/2013/10/lou_read_obit_an_appreciation_of_the_velvet_underground_frontman.html

Similar Articles: james taylor

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.